Rushed, relegated and reprimanded: The quiet crisis in journalistic games reviewing

The rise of creator reviews has shifted power to publishers, giving them unprecedented control over games journalists.

Infinite Lives is a reader-supported publication. It’s free to sign up and read the latest piece, but as of July a subscription will be required to read my backlog of over 70 unique articles. Each subscription goes towards improving this Substack, supporting the broader Substack gaming community and funding more independent games journalism in Australia.

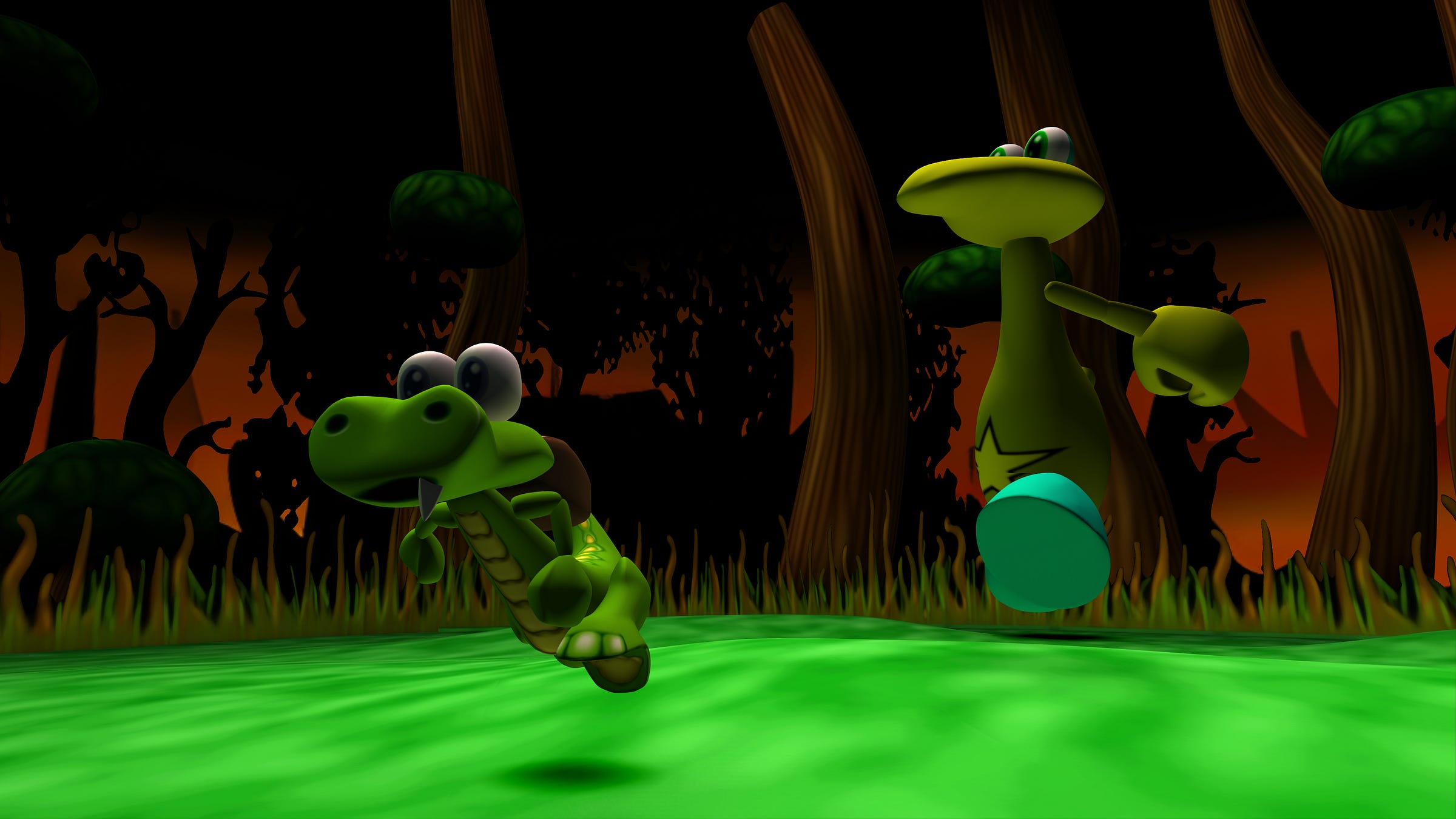

Ben Schuster was at his wit's end. The editor of Qualbert, an Australian gaming news and review website founded in 2021, was negotiating for access to a review code for Croc: Legend of the Gobbos Remastered.

Given it was a remaster of a classic '90s PlayStation game, he thought there would be ample appetite among his audience for a review and one of his writers was keen on the job. But the reply the pair received from the game's developers shocked Schuster.

"The response from the devs was hostile," Schuster said. "They accused me of trying to scam them for a code to resell."

"All they had to do was click the link in my signature to see we're legit. I understand the concern—Steam devs get bombarded by scammers. But it was unpleasant," he says.

Schuster explained that while over the top, the reply wasn't completely unwarranted. Using content platforms, scammers create fake review sites and then hit up developers for codes. Qualbert, however, was shortlisted for two Lizzies Australian tech journalism awards this year.

A spokesman for Croc: Legend of the Gobbos Remastered confirmed the email exchange with Qualbert, but says their requests for a code were ignored due to the influx of interest from press and human error.

In the modern game review dynamic, proving legitimacy is just one of many challenges.

This year, Infinite Lives delves into the broader issue of video game reviews, asking whether the way in which games are assessed needs to change. In this edition of the series, we put the question to traditional media — journalists who, as part of the greater public interest, review games ahead of launch, provided they get access to them.

It's an inside-baseball topic that isn't really covered by the games media itself. Launch reviews are major drivers of traffic for gaming websites, and are often the foundation for readers going to them in the first place. But the rise of content creators in this space, and the drive from publishers and developers to have their game stand out from the crowd, has complicated the way reviews are conducted.

The level of control described to me across several discussions with media on this topic — both on the record and on background — would be considered unacceptable by many other fields of culture-based journalism. While reviewer impartiality is always maintained, through the veiled threat of removing access for future games, major publishers can dictate when a review goes live. They can also manipulate the amount of time reviewers have to conduct their work, expecting, for example, that a 100-hour role-playing game can be reviewed in less than a week.

There's no industry standard professional reviewers can fall back on. Reviewers are generally penalised by both traffic numbers and future access restrictions.

With creators eroding their importance and mainstream media appetite for gaming content waning, the power balance dictating the review process for major games is faltering. Meanwhile, indie titles still struggle to catch the attention of a diminishing number of game reviewers left in the press.

Qualbert's founder Ben Schuster and co-editor of the Press Any Button Substack and winner of this year's Best Gaming Reviewer Lizzie Award, Alice Clarke, went on the record to discuss this dynamic, the status quo and what can be improved.

The price of non-compliance

Perhaps the most startling revelation of these discussions is the indirect power publishers and PR teams can hold over reviewers. The most overt form of this is an embargo date whereby the reviewer is expected to have their review go live on that particular day, regardless of when they receive the game.

"If I get a 100-hour RPG a week before embargo, I can either do a rushed, incomplete review — or miss embargo and lose relevance," Schuster says.

"I've been penalised before. Not just in traffic, but in terms of future access. Some PR teams have said outright: 'You missed the embargo, so we can't prioritise you next time.'

"That's tough, especially for indie outlets who do this in their spare time. There needs to be more leeway, especially for long or complex games."

Despite writing for mainstream outlets like The Age and Herald Sun as a freelancer, Clarke says she's also felt pressure to meet the embargo deadline, to ensure her work is news relevant.

“I wish so many critics didn’t have to rush reviews to be live by an arbitrary date just because so many people believe reviews lose value after embargo.”

“Often, when a publisher gives you basically no time to play a game for review, it’s often because they either know it’s not good, or because it’s simply not ready yet and the developers are crunching, which also means it’s probably not going to be the best. It’s an open secret at this point. Sometimes the game turns out to be amazing, but that’s rarer. I think most publishers understand how it looks when they don’t give us enough lead time.”

So how much lead time should you give for a review? Clarke offers a broad guideline of a week or two for a short game, and up to a month for a larger RPG title that spans over 50 hours.

"Reviewers are paid terribly and expected to work in crunch conditions," she says.

"That's not sustainable. If you want critics to stick around, respect the time and effort involved. Games should be treated like film or music — criticism is a craft, and critics need time to do it properly."

Give it a score

Beyond pressure to have reviews out at a certain time, journalists are also pressured into giving games a score out of 10. It's a contentious issue across the gaming media; Polygon famously axed scores from their website back in 2018, and other sites have followed suit.

There are two major mechanisms behind this: Firstly, publishers use these scores to market games in accolade trailers after the release. Being featured in those trailers helps the news site's legitimacy and markets them.

Secondly, sites like Metacritic aggregate review scores and can serve traffic to games websites — but only if they give it a score.

“I can see how Metacritic has its place. Some people just like numbers, and getting an aggregate score can give an indication of the quality of a game," Clarke says. "Scores help summarise, especially when readers don't have time to read the full review."

"But scoring is broken. A 7 became the 'average', and anything below a 9 can cause outrage from ‘The Gamers’ and certain PR people. A 5 should be average, and it’s normal for games to fall on the full scale. Besides, reviews are so subjective, you don’t want everyone to say everything is amazing, because that’s not real."

"Access-driven journalism means some reviewers are scared. To be clear, I am not. I have been lucky to have mainstream backing for most of my career — I could say what I wanted, and I still won’t compromise my opinion to make a PR person happy, because my priority is always the readers, otherwise what is even the point of writing anything? That's not the case for everyone," she adds.

Meanwhile, Schuster says that Qualbert has been denied review copies or cut out of accolade trailers because of their reluctance to provide a score.

"Too many PRs, devs, and publishers reject us because we're not on Metacritic — and we're not on Metacritic because we don't use scores," he says. "It's a shame. We believe in matching games to players, not assigning arbitrary numbers. I know it's a disadvantage, but I'm not changing that."

Schuster however points to OpenCritic as a path forward for the industry. It showcases a number of reviews that both do and don't provide a score.

Views on creator reviews

The other factor pincering media reviews is the proliferation of creator-led content on gaming, giving publishers more choice in how to shape the critical reception of their title.

While creators are beholden to the whims of their audience, there are broader concerns among gaming journalists that their impartiality is stifled by other commercial arrangements with publishers.

Clarke offers a more pragmatic distinction.

"Creators often blend content and monetisation. Journalists avoid that — they don't touch the money," she says. "Those lines shouldn't be blurred. Both have their place, but they're fundamentally different."

As for what that place is, Clarke says the mainstream media helps bring games to a much broader audience that might not be served by creators.

"Most people who buy games just want to know if the game is good," Clarke says. "They don't care about their personalities. For example, a dad buying a game for his kid's birthday, or a mum who only has an hour a week to play — those people are just looking for a quick, trustworthy recommendation. They'll go with the first review that looks legitimate from a site they know."

Meanwhile, Schuster says creators play a fundamental role in surfacing indie and emerging games to their audience.

"For smaller devs, getting a game to blow up with creators can be more effective than traditional press," he says.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Infinite Lives to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.